Eduardo Marisca | 16 Jan 2014

So I found myself referencing the concept of the “technological sublime” repeatedly, without having actually stopped for a moment to consider what I was talking about. Only then did I realise it was not the spoon that bent, it was only myself — that is, I realised the category was not as commonplace and clearly defined as I assumed it to be, and decided to go down the rabbit hole to pinpoint more clearly what I was trying to say when summoning the technological sublime as a conceptual Pokémon.

In doing so, I discovered that there was not one, but many different versions of the sublime that had been referenced and discussed in various areas of literature and research. And pushing things a bit further, it was perhaps not surprising that the common ground for many of these was the notion of the sublime described by Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Judgement, where, amongst many things, Kant discusses matters of aesthetics, creativity, and what it means for something to be beatiful or, alternatively, sublime. Kant’s concepts of the beautiful and the sublime — of which you can surely find much better descriptions than the ones I’m providing here — are related to an individual’s faculties and how they’re variously affected by aesthetic phenomena. As opposed to the workings of intellectual understanding, which takes sensory experience and subsumes it systematically under categories that enable one to connect judgements and statements to a previously accrued body of knowledge, the aesthetic experience begins precisely by being impossible to categorise and introducing some form of malfunction in the operations of intellectual understanding. Thus, it is not possible — at least at first — to entirely reduce aesthetics to conceptual relationships. Kant described the experience as being alternatively beautiful, providing the sensation of one’s faculties being perfectly aligned and in harmony, or sublime, providing the opposite sensation of one’s faculties being entirely out of control and overwhelmed. He illustrated the experience of the sublime as arising from the contemplation of the vastness of nature — an open ocean, an exploding volcano, a gigantic mountain — and the sudden feeling of being entirely overwhelmed by the world.

That’s a very rough description but, I hope, a helpful one. It is part of the aesthetic experience, either sublime or beautiful, that it cannot be eternal — intellect eventually catches up and domesticates that which is alien, foreign, overwhelming, into categories that allow for its manipulation and assimilation. There are similar processes taking place in Lacanian psychoanalysis (of which I’m also not an expert): the sublime is akin to the manner in which the order of the Real disrupts the symbolic order. Experiences of the Real (which in Lacanian jargon are different from “real experiences”) are experiences of that-which-cannot-be-named and leave us at a loss for words desperately trying to come up with explanations and rationalisations. The symbolic order, that of language, is shattered by these experiences, and is only restored when we can put a name on that-which-cannot-be-named, domesticating through rational understanding.

The experience of the sublime is understood to be a transformative experience, even if only mildly in some cases: experiencing the sensation that one’s own faculties and capacities are being entirely overwhelmed beyond explanation becomes a stressing of those same faculties and capacities to the point where they can assimilate and process that experience. The subject that experiences it is qualitatively different after going through it.

The experience of the sublime, however, is not just something that “happens”, or as Kant described, found only in nature. The sublime can be constructed, deployed, and circulated in various rhetorical configurations that mimic this same capacity of overwhelming the faculties of those experiencing it. Architecture, for example, can in various ways appeal to the sublime or attempt to recreate the sensation of it in order to instill in people specific feelings and emotions. Films and music can also in many ways craft such experiences, crippling a subject’s capacity to fully understand what’s going on right away. And because these experiences are transformative, the emotional appeal of the sublime also lends itself quite readily to political transformation. Political rallies and events work not because they’re effective means to communicate specific ideological content to an expecting audience, but rather because the mass experience so overwhelms a participant’s understanding that the connection, rather, operates at a much more emotional level. Through the experience of the rally one is bound to a community and made a part of a larger cause: it is very much an experience of the sublime, even if an entirely artificial and interested one. Which means that the sublime can be intentionally deployed, and that deployment takes place through complex emotional rhetorics — but this doesn’t necessarily imply that such intentional deployments of the sublime always respond to the interests and beliefs of specific individuals or groups, or that their rhetorics are always deployed in conscious fashion (nor does it imply the opposite either).

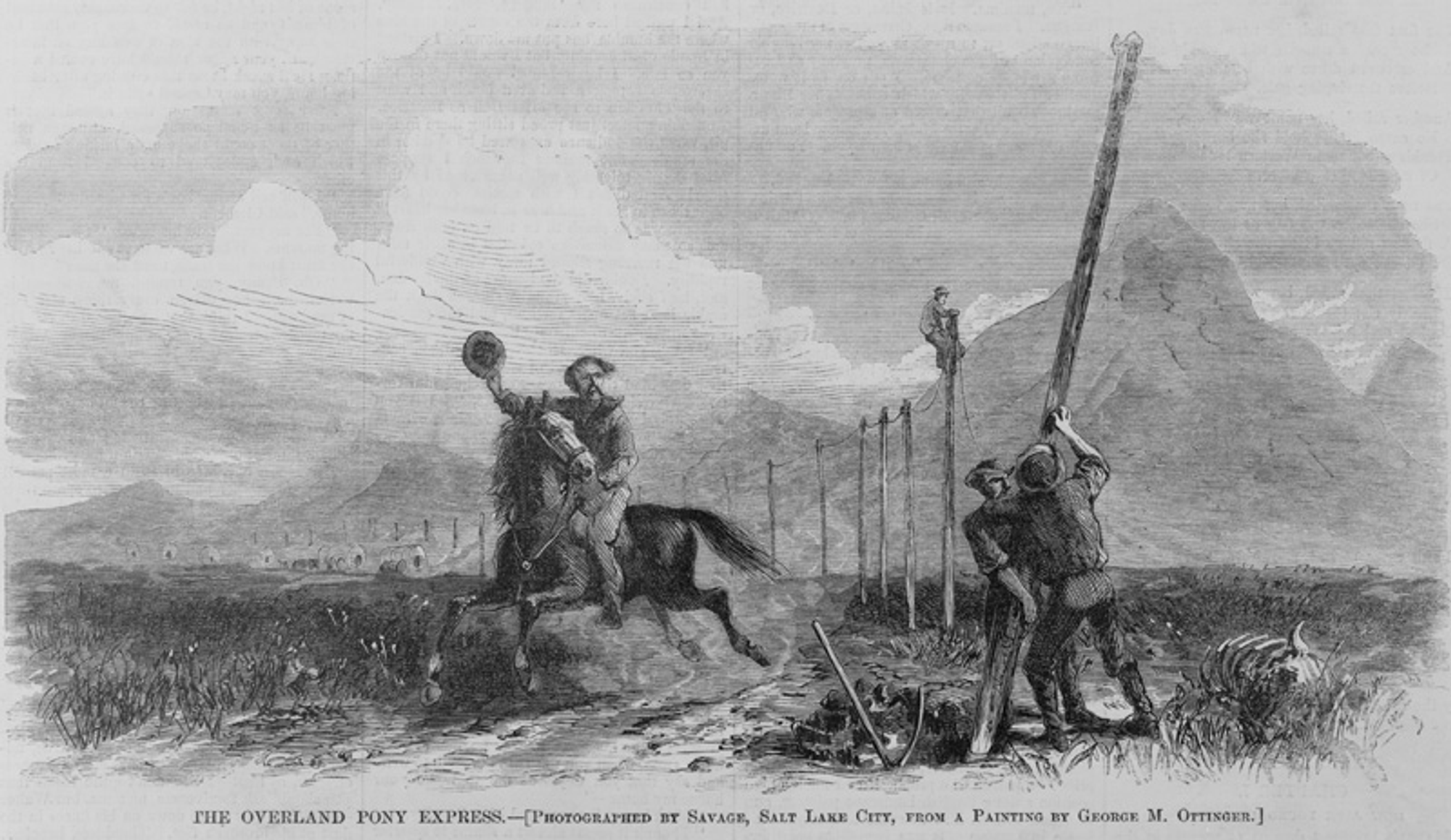

From the 19th century, the belief began to emerge that great societal transformations could happen through technology — that the introduction and deployment of new technologies could bring about new eras of not only material prosperity, but also cultural and spiritual enlightenment. These ideas were not entirely new, and can be clearly anchored in the consciousness of Modernity that had already been brewing for a couple centuries, but they began to fully take shape and to circulate hand in hand with specific forms of new technology by the time of the 19th century — in the Northern hemisphere and the Western world, especially just as technology began to play an unprecedented role in the Civil War in the United States, where multiple innovations introduced not only in the battlefield but especially behind the scenes, in the supply lines, would result in huge transformations in terms of mobility, productivity, and social relations. It was during the 19th century that the belief that technology could bring about a new society became embodied in actual technologies being deployed worldwide, and that began articulating the “rhetoric of the technological sublime”, as described by Leo Marx in his classic book The Machine in the Garden and later appropriated by researchers such as James Carey. Carey describes the emergence of this rhetoric as closely connected to the technical deployments of the telegraph and the railroad:

Like most intellectuals of the period, this group [John Dewey, George Herbert Mead, Robert Park, Charles Cooley & Franklin Ford] was under the spell of Herbert Spencer’s organic conception of society, though not enthralled by social Darwinism. The relationship between communication and transportation that organicism suggested—the nerves and arteries of society—had been realized in the parallel growth of the telegraph and railroad: a thoroughly encephalated social nervous system with the control mechanism of communication divorced from the physical movement of people and things.

They saw in the developing technology of communications the capacity to transform, in Dewey’s terms, the great society created by industry into a great community: a unified nation with one culture; a great public of common understanding and knowledge. This belief in communication as the cohesive force in society was, of course, part of the progressive creed. Communications technology was the key to improving the quality of politics and culture, the means for turning the United States into a continental village, a pulsating Greek democracy of discourse on a 3,000-mile scale. This was more than a bit of harmless romanticism; it was part of an unbroken tradition of thought on communications technology that continues to this day and that Leo Marx (1964) named and I appropriated as the “rhetoric of the technological sublime. (Carey, 2008, p. 110)

From this we can gather more clearly what a “technological sublime” is about: a rhetorical construction of a substantive, qualitative transformation brought about by the introduction of one or more specific technologies that will enable a “leap forward”. When we hear about how introducing computers into the classroom will transform education, we’re facing a version of the technological sublime. Similarly, when the advertisement for a product makes the claim that distant loved ones will feel closer through some new mobile communication technology, we’re also facing the technological sublime. When we hear arguments about how connectivity and Internet access will empower the disenfranchised masses and connect excluded populations with the rest of the world, we’re also facing the technological sublime. What all of these are saying is, essentially, “if we could only get this technology in place, then X wouldn’t be a problem anymore”.

Of course, these rhetorical constructions are complex and contested, with multiple forces struggling over exactly what technology or technologies will be able to do this, or diagnosing exactly what the problem is that will magically go away. And while they can be construed as promising utopias of desirable futures, they can also be abused as forms of oppression and othering. Brian Larkin, for example, writes about a different version of the technological sublime he identified while researching the media practices of filmmakers in Nigeria, and how historical relationships with technology have been molded by a “colonial sublime”, a similar construction of that which is overwhelming put to the service of an imperial power to exert symbolic domination over a colonised population. During Nigerian colonial rule, the technology was used to discipline behaviour, both to convey what the colonised did not have on their own — bridges and railroads and radios and so on — and what they could potentially become if they played along with colonial rule. The colonial sublime, and the technological sublime, can be both the carrot and the stick.

In my specific research, the technological sublime is playing an important role in understanding how these constructions have evolved over the course of Peruvian republican history, as succesive instantiations of the rhetoric of the technological sublime have become drivers of the belief that a nation can be brought together through the introduction or deployment of new technologies. This belief, however, has consistently failed to materialise over and over again. In looking at the video game industry, I’m trying to make the argument that video game creators have managed to sidestep the “official” rhetoric regarding technological development to craft one of their own, that works on their own terms, even if their own interpretation often comes into conflict with the official narrative of the nation’s technological future. But this ground-up narrative may be able to establish a more sustainable relationship with technology that is not only not contingent on external forces driving the country’s history, but also better suited to the specific technology needs and wants of the nation. Maybe.

References

Carey, James W. 2008. “Space, Time, and Communications: A Tribute to Harold Innis.” In Communication as Culture, Revised Edition: Essays on Media and Society, 2 edition, 109–132. Routledge.

Kant, Immanuel. 2007. Critique of Judgement. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Larkin, Brian. 2008. Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press.

Marx, Leo. 2000. The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. Oxford University Press.

Nye, David E. 1996. American Technological Sublime. MIT Press.